Court of Appeal upholds non-infringement finding in respect of Garmin watch sensors

The Court of Appeal has recently handed down its latest judgment on Community designs (PulseOn OY v Garmin (Europe) Limited, [2019] EWCA Civ 138). This appeal arose from a High Court decision of Roger Wyand QC (sitting as a Deputy High Court Judge) in which he held that two Registered Community Designs (belonging to PulseOn) protecting the arrangement of LEDs/photo sensor for a wrist heart rate monitor were valid, but were not were not infringed by Garmin’s own design used on certain of its sports watches.

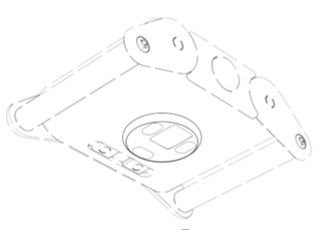

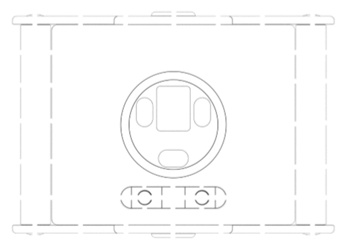

The representations from one of the RCDs are shown below:

As per EUIPO’s Guidelines for Examination of Registered Community Designs, features for which protection is not claimed are shown in dotted lines. Thus, the RCD only sought to protect the shape and arrangement of the three oblong LED sensors, the rectangular photo sensor and the circular platform. (There was some discussion as to whether the small screws which secure the bar to which the wristband is attached, and which appear not to have been depicted in dotted lines, were intended to be included in the scope of protection. The judge held that they were excluded, essentially as an obvious mistake.)

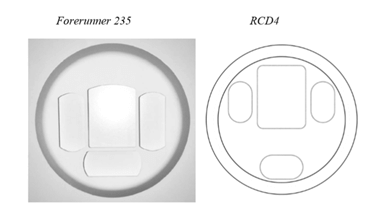

A model of the allegedly infringing Garmin design (from its Forerunner 235 device) is shown below alongside the protected elements of the aforementioned RCD:

The judge concluded, taking into account the features which he felt were common in the design corpus for this kind of product and the limited design freedom (due to various functional requirements) that, on the balance of the similarities and differences between the respective designs, the Garmin design did not infringe the RCD.

PulseOn appealed this decision to the Court of Appeal (CA) on various grounds:

• Ground (1): the judge had erred by concluding that design freedom was more constrained than it actually was. The CA agreed that the judge may have stated the design freedom a little more narrowly than he should have done in relation to one particular feature, but that did not result in the RCDs being afforded a significantly wider scope of protection than they should have had. The judge’s conclusion that there was limited design freedom was still materially correct.

• Ground (2): the judge had erred by comparing an enlarged 3D model of the Garmin product to the RCD, rather than the Garmin product itself. PulseOn argued that the decision to compare the RCDs to the model (rather than the product itself) resulted in an exaggeration of the perceived differences, which were scarcely noticeable when a comparison with product was carried out. The CA found that, whilst normally the comparison should be between the RCD and the product itself, in this case it was justified to depart from this approach and compare the RCD to an accurate model of the product. This was because a comparison of the RCD with the actual product was hampered by the fact that they are extremely small, and by the fact that the eye was drawn to what was behind the LED/photo sensor apertures (which was not within the scope of protection of the RCD) rather than the apertures themselves. Models of the apertures, provided they were accurate, overcame these difficulties.

• Ground (3): the judge erred in attaching undue weight to certain features which were determined by technical considerations. The CA held that the judge must have been aware of the reason for the differential spacing between the different LEDs and the sensor (a feature which was impacted by technical consideration), and the weight to be given to this in his overall evaluation was a matter for him. It had to be balanced against the fact that the spacing was not amongst the features found, either commonly or at all, in the design corpus, and was therefore entitled to more weight in the assessment exercise for that reason. There was no reason for the CA to interfere with that assessment.

• Ground (4): the judge erred by asking whether the Garmin design produced an “identical impression” on the informed user as the RCD, rather than whether it produced a different overall impression on the informed user. The CA found that despite using imprecise terminology at certain points in judgment, the judge had properly directed himself as to the correct test for infringement and it was is quite clear that the judge had in mind throughout the correct test and applied it.

Conclusion

This case emphasises the point that where, as here, the protected designs relate to highly functional or technical products (or parts thereof), the restraints on design freedom caused by the technical/functional requirements will result in correspondingly smaller design differences serving to create a different overall impression on the informed user. This is because the informed user is taken to be aware of these design freedom constraints (although not necessarily all the engineering considerations underpinning them because the informed user is not an expert engineer), and so affords similarities resulting from such constraints less weight in the overall impression created by the design. The upshot is that, all things being equal, a greater degree of similarity is normally required to infringe the design of a highly functional or technical product than might be the case for the design of a highly decorative/aesthetic product.